Boston History

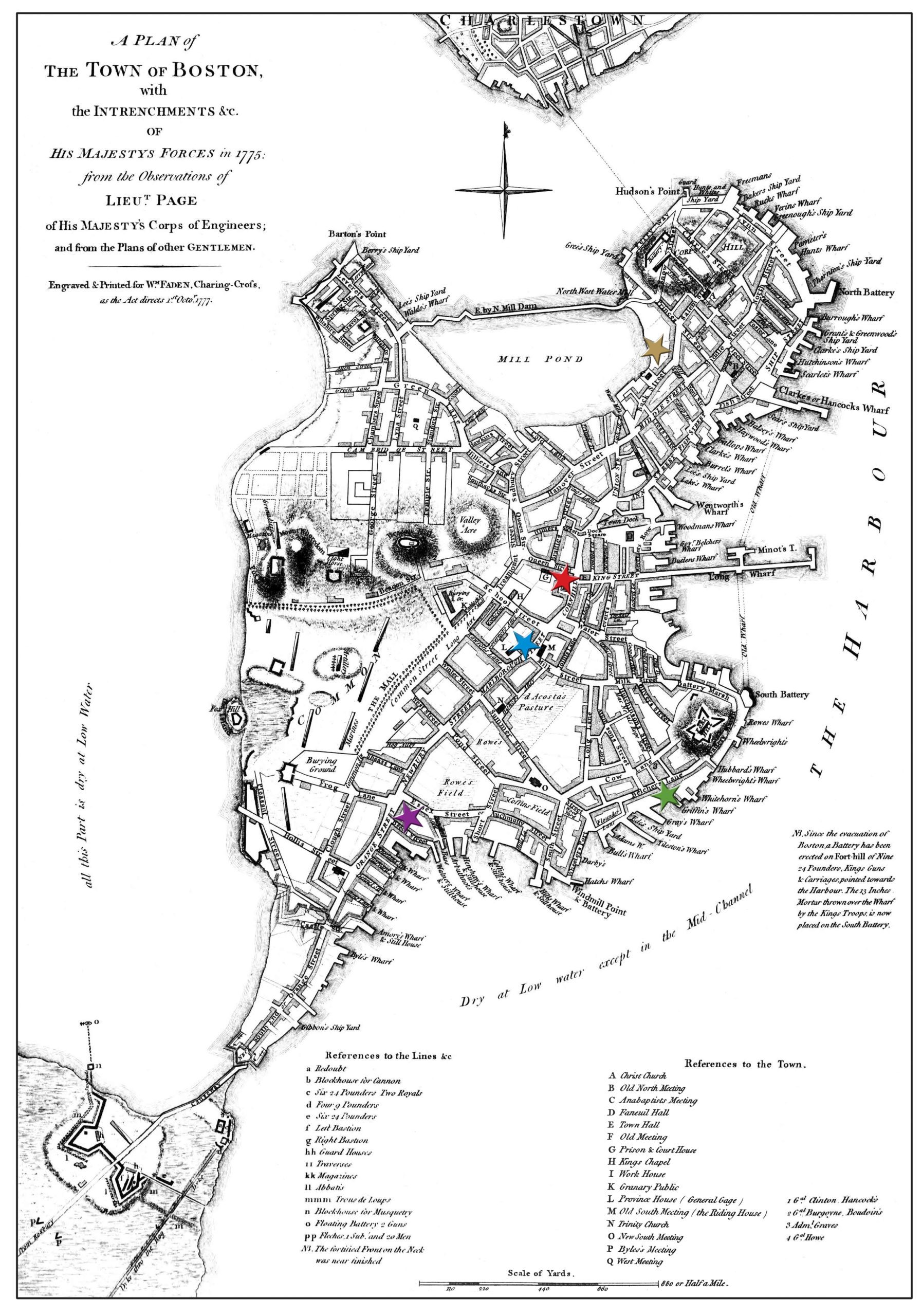

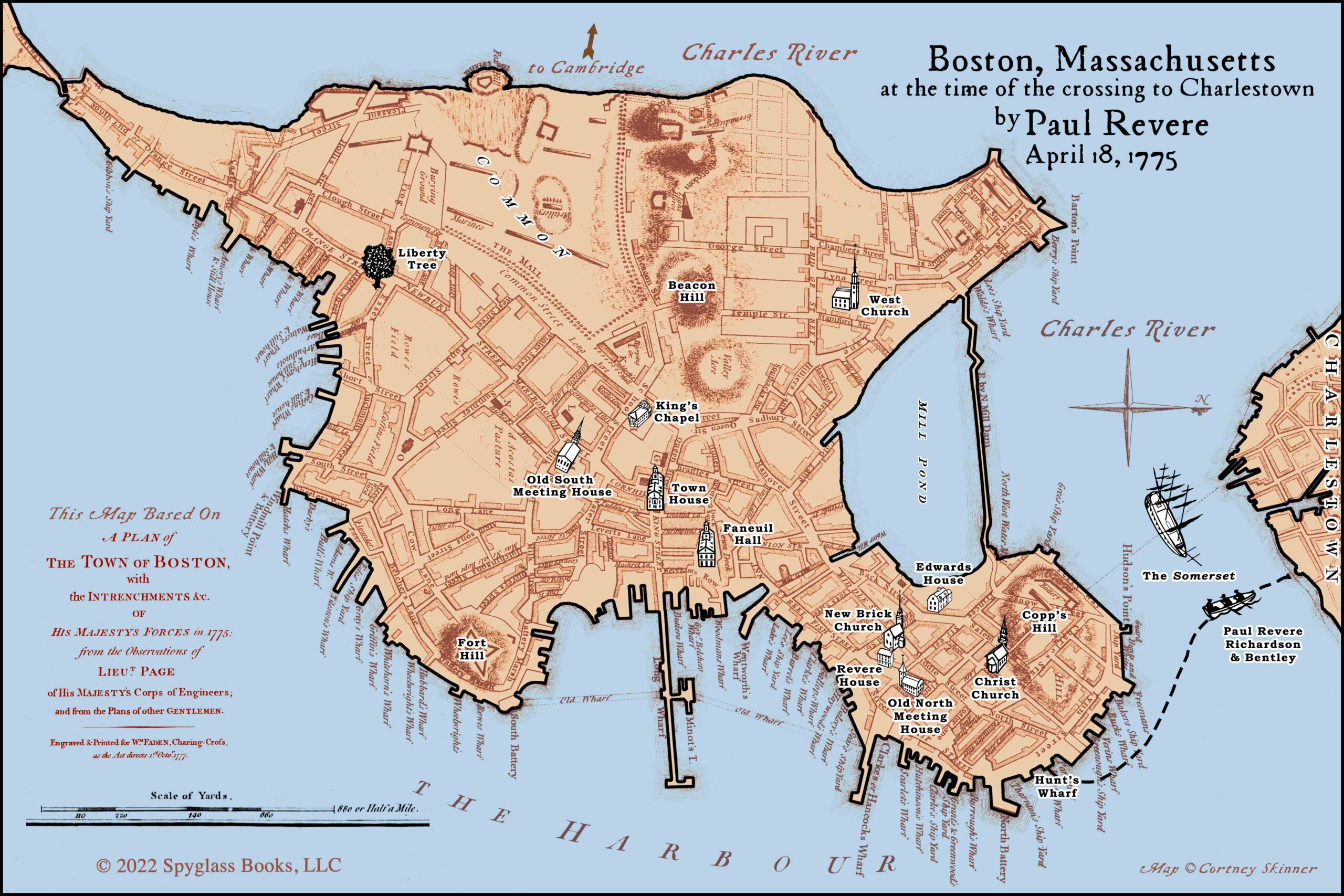

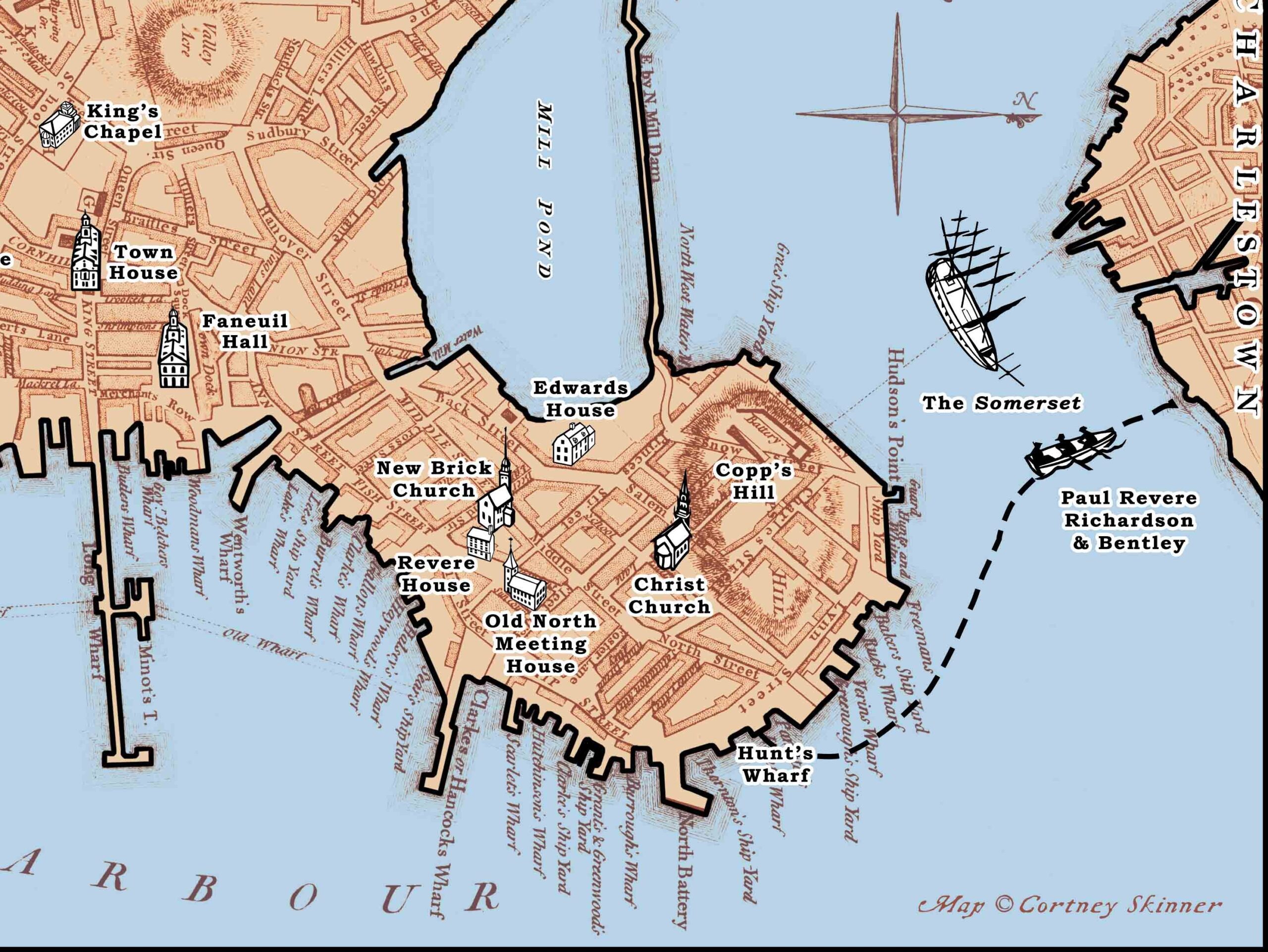

Maps of Boston – 1775

Colonial Boston at the time of the American Revolution

Scroll to: Back Street Black History

Click maps for high resolution image.

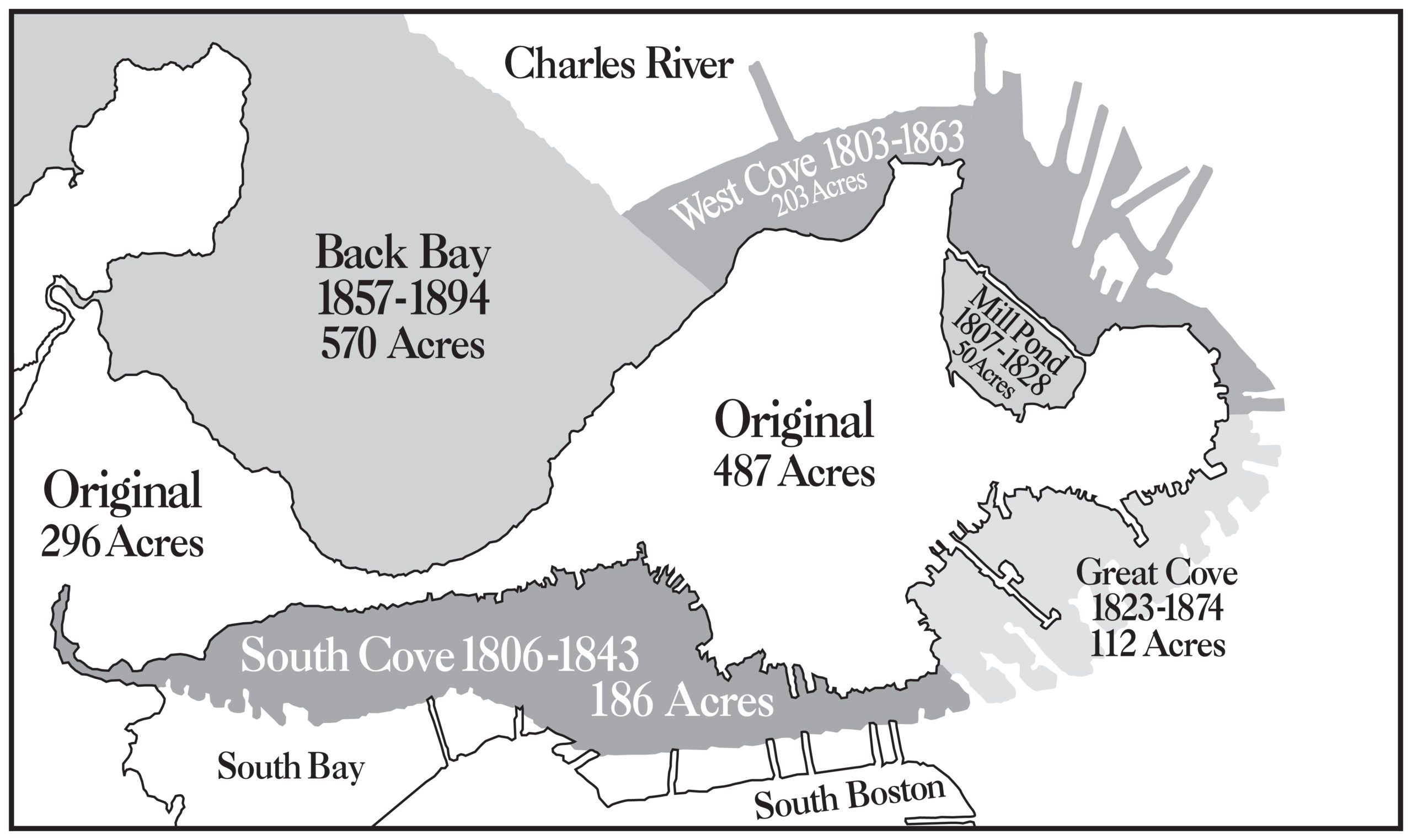

A map showing the original 783 acres and the areas of made land

Boston History

Key events in the history of Boston

Stamp Act – March 22, 1765

The first direct tax on the American colonies. Taxed items included legal documents, newspapers, dice, and playing cards. It was repealed in 1766.

Townshend Acts – June 29, 1767

This act of Parliament imposed duties on glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea imported into the colonies. All were eventually repealed except for the tax on tea.

Landing of the Troops – September 30, 1768

British warships, armed schooners, and transports arrive and anchor in Boston Harbor. The following day two regiments of British troops (upwards of 700 men) land at Long Wharf, march into town, and begin their occupation. Engraving by Paul Revere.

Boston Massacre – March 5, 1770

British soldiers fire on a crowd in front of the Town House killing five men – three died at the scene and 2 died later. Engraving by Paul Revere.

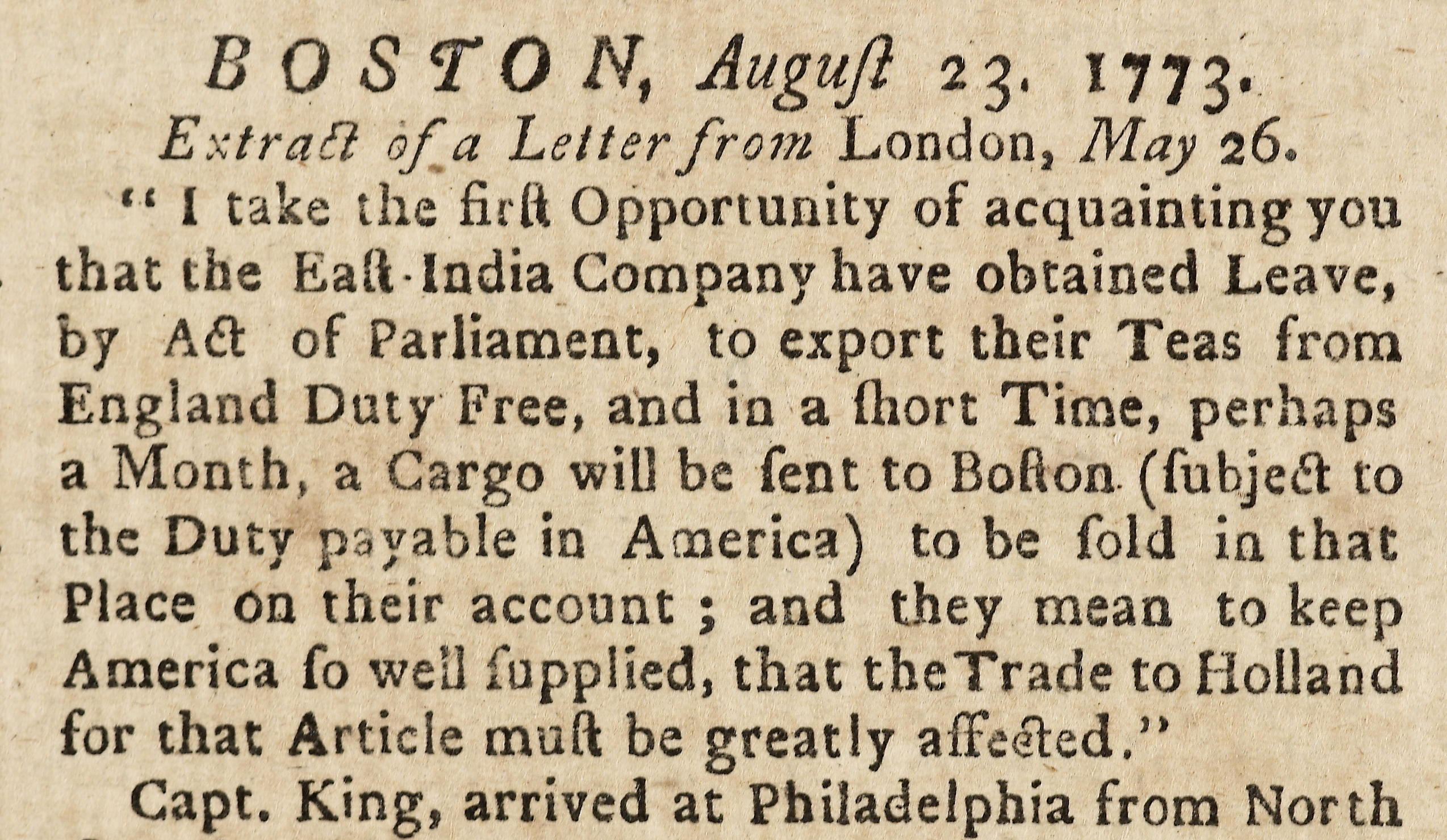

Tea Act – May 10, 1773

Gave the British East India Company a monopoly. The company had the right to ship its tea directly to the colonies without first landing it in England, and to commission agents who would have the sole right to sell tea in the colonies.

Boston Tea Party – December 16, 1773

A group of colonists (to date, there are 116 documented participants) board three merchant ships (Dartmouth, Eleanor, and Beaver) docked at Griffin’s Wharf and dump 340 chests of tea into Boston Harbor.

Coercive Acts – March-June, 1774

A series of five laws passed by the British Parliament to punish the Massachusetts Bay Colony for the Boston Tea Party. Among these was the Boston Port Bill, which closed the Port of Boston until damages from the destruction of the tea were paid.

Paul Revere and William Dawes ride – April 18-19, 1775

Learn the details of that famous night and view the video “Paul Revere’s Ride – The Real Story.”

Battle of Bunker Hill – June 17, 1775

The Declaration of Independence is read in Boston – July 18, 1776

From the balcony of the Town House, today’s Old State House, the Declaration of Independence is read to the citizens of Boston on July 18, 1776. An illustration of the event from One April in Boston and an audio excerpt from the Independence chapter follows.

Independence Chapter Excerpt

Back Street

In the footsteps of Ben’s ancestors

Alexander Edwards (1733-1798) lived on Back Street. He was a cabinetmaker and a member of the Sons of Liberty.

This map of the North End of Boston in 1775 shows the location of the Edwards family home on Back Street.

The lower portion of Salem Street (formerly Back Street) as it appears today. The Edwards property was on the left.

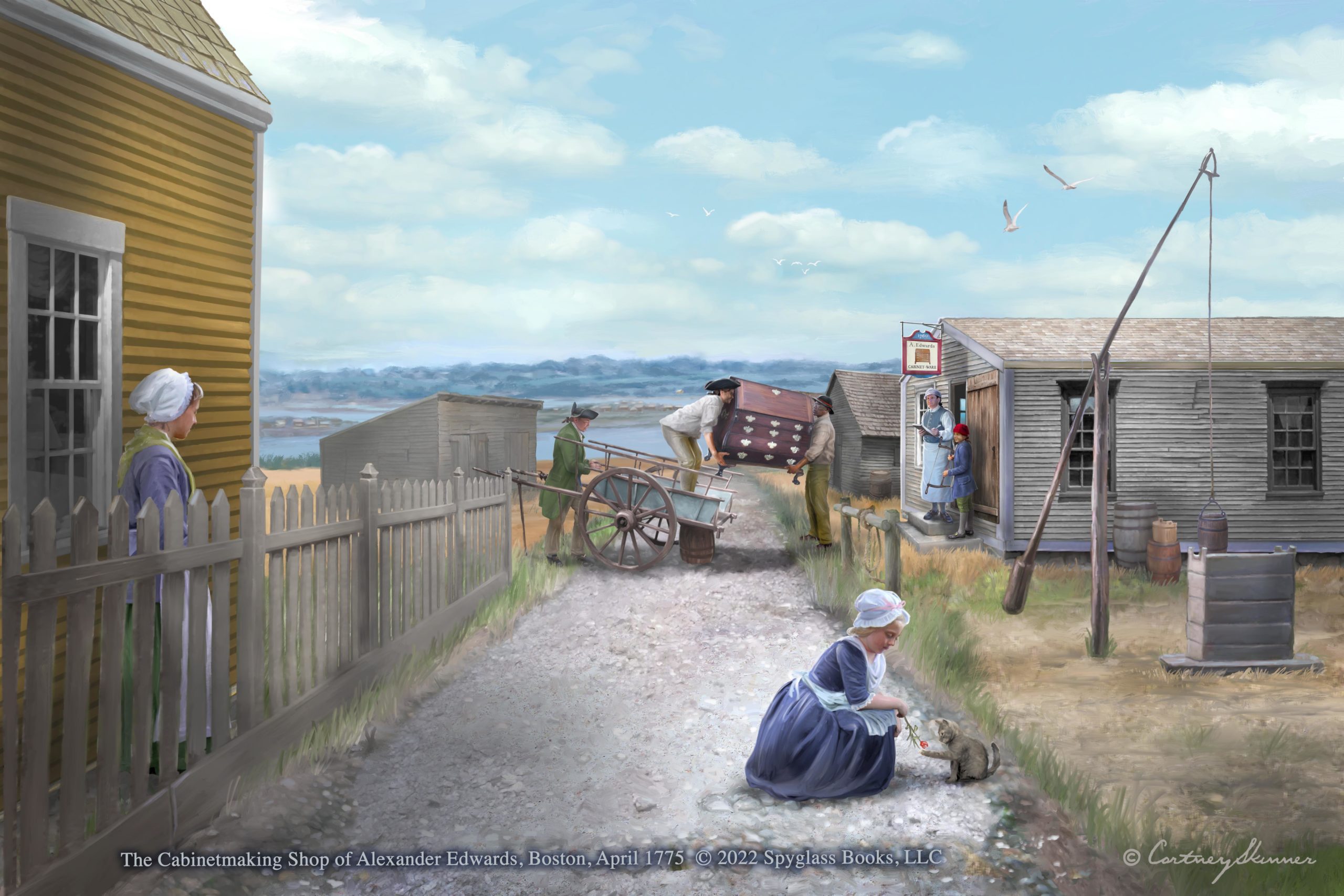

This painting by Cortney Skinner shows the Edwards home (at left) on Back Street as the street may have looked in April 1775. Cortney’s research for the artwork was aided extensively by “Clough’s Atlas – Property Owners of the Town of Boston based on the Direct Tax Census of 1798.”

The home of Alexander Edwards (1733-1798) and his wife Sarah Greenough Edwards (1735-1823) is shown on the left, and next to it their stable and Alexander’s cabinetmaking shop.

Walking down the eight-foot-wide passageway (Cooper Street today) we see a portion of the Edwards family home on the left and the cabinetmaking shop of Alexander Edwards on the right.

The Sons of Liberty

The signature of Alexander Edwards on the Boston Citizen’s Non-Importation Agreement of July 31, 1769.

Alexander Edwards’ name appears on this list of the Sons of Liberty who dined at Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester, Massachusetts on August 14, 1769.

Acorn Street

Acorn Street in Beacon Hill is Boston’s oldest surviving cobblestone street. It was laid out in 1823 and the nine brick row houses that line the street were built by architect-builder Cornelius Coolidge between 1828 and 1829. Back Street may have been paved like Acorn Street. Photo by Ben Edwards.

Black History

Key figures, sites, and memorials related to Boston’s Black history that we discuss during the tour.

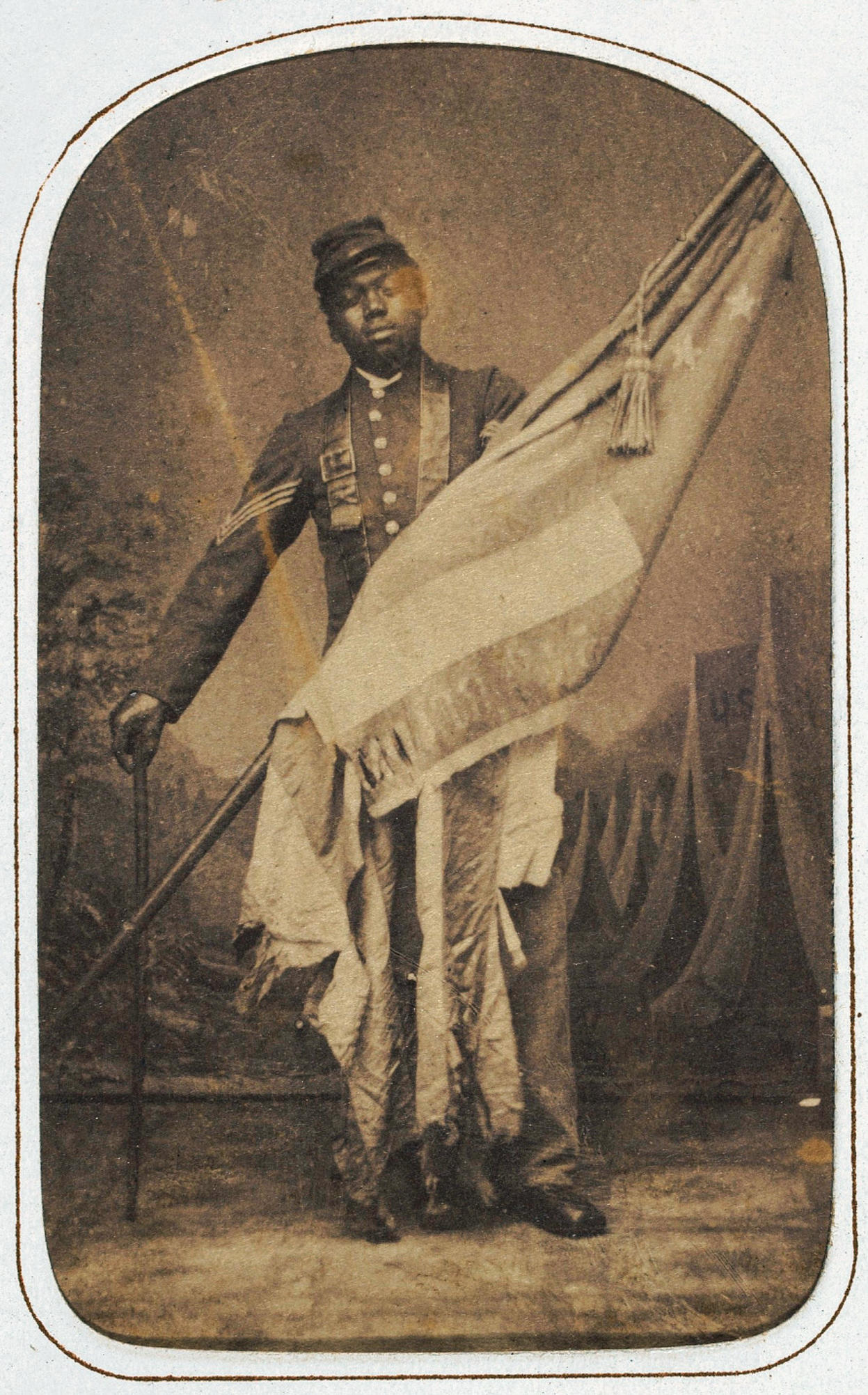

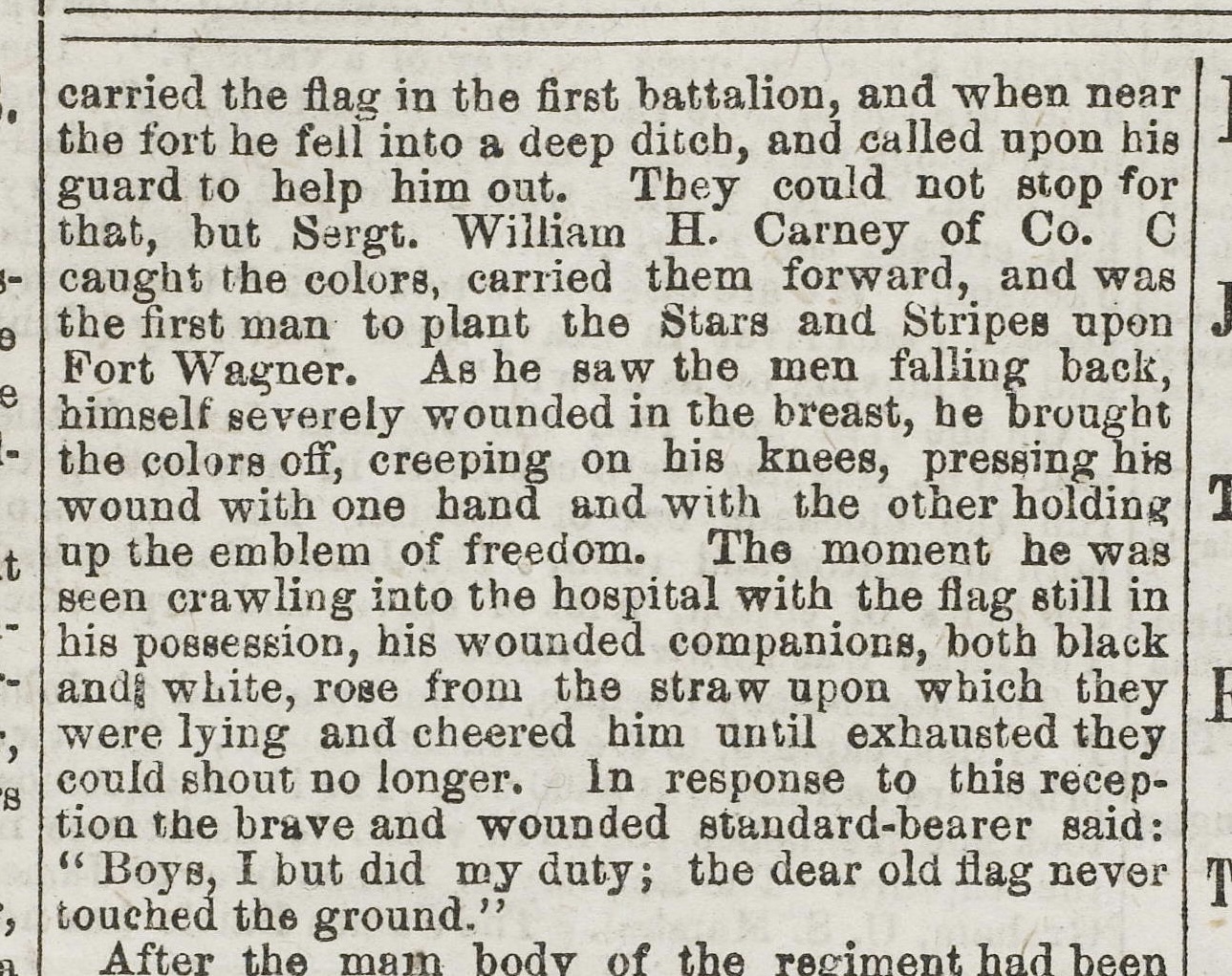

Sgt. William H. Carney

Sgt. William H. Carney holding the American flag, ca. 1864

William H. Carney (1840-1908) was born a slave in Norfolk, Virginia. His exact route to freedom is unclear. Some accounts say he escaped through the Underground Railroad and joined his father in Massachusetts, while others say Carney’s father purchased his son’s freedom after escaping via the Underground Railroad himself. The family eventually settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts. William H. Carney enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment in early 1863. On May 23, 1900, he received the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions during the assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863. Details of Carney’s courageous conduct appear below in the August 3, 1863 issue of the New-York Daily Tribune.

Illustration of Phillis Wheatley by Scipio Moorhead

Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753-1784) was born in West Africa and kidnapped and sold into slavery at the age of 7 or 8. She arrived in Boston on July 11, 1761 and was bought by the Wheatley family. After Phillis learned to read and write, they encouraged her poetry. Phillis was brilliant. She became the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry when her work Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was published in London in 1773.

In 1775 Phillis sent a letter to General Washington and included a poem she had written for him. Washington replied in 1776 and invited her to visit him at camp in Cambridge. It is not known whether Wheatley and Washington ever did meet in person.

To George Washington from Phillis Wheatley, 26 October 1775

The Poem Phillis Wheatley sent to George Washington, 26 October 1775

Letter from George Washington to Phillis Wheatley, 28 February 1776

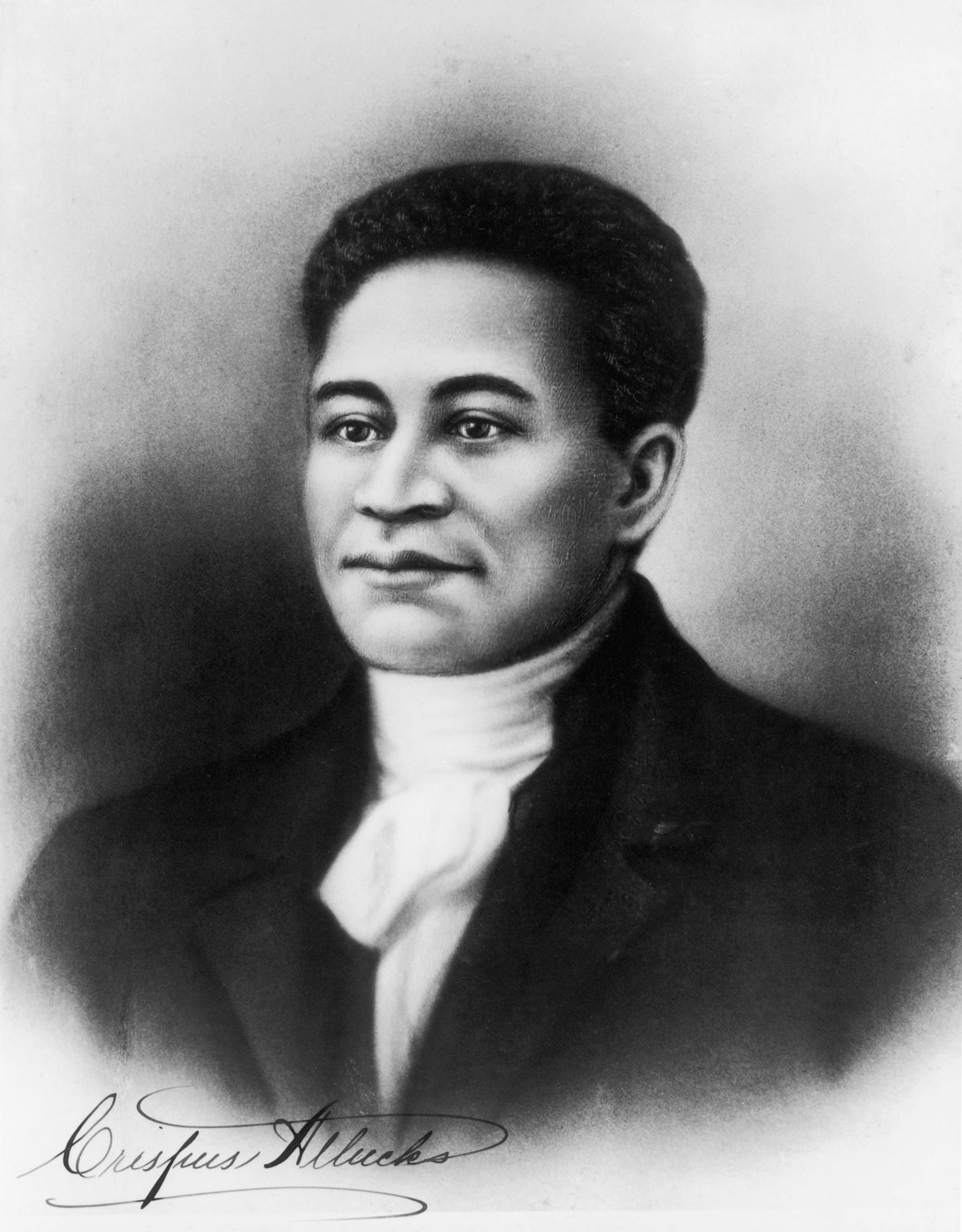

Crispus Attucks

A speculative portrait of Crispus Attucks

Crispus Attucks (c. 1723-1770) was the first person shot and killed by British troops in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. Attucks was a runaway slave and a sailor of African and Native American descent. Intriguing details of his story are told in these excellent blog posts from J. L. Bell’s Boston 1775 blog.

The Brown Family Memories of Crispus Attucks

More Information About the Attucks Family

The Last Relics of Crispus Attucks

Prince Hall

Prince Hall’s marker at Copp’s Hill Burying Ground

Prince Hall (1735-1807) was the slave of a Boston leather worker who was granted his freedom in 1770. He then operated a successful leather store himself. On March 6, 1775, Hall and 14 other free Black men were initiated into freemasonry. They organized African Lodge No. 1 on July 3, 1776. In 1784 they petitioned the Grand Lodge of England for a charter; it was granted and African Lodge No. 1 became African Lodge No. 459 of Boston, Massachusetts. This organization laid the foundation for African American citizenship, education, and for the improvement of the condition of Blacks. Prince Hall Freemasonry is the oldest recognized and continuously active organization founded by African Americans.

Masonic Education – Prince Hall

Boston Slavery Exhibit

This exhibit in Faneuil Hall details the history of slavery in Boston. It tells the complete story, addressing both Native enslaved people and Africans and is intended to be a starting point for Boston to talk about its history of slavery — this according to Joe Bagley, Boston’s City Archaeologist. It is part of a larger project to digitize over 60,000 artifacts found by the archaeological surveys at Faneuil Hall and make them accessible online.

Boston Slavery Exhibit – Online Edition

King’s Chapel Memorial to Enslaved Persons

The Memorial, recently approved by the church, honors 219 men, women, and children who were enslaved by congregates of King’s Chapel.

The $2 million project will transform the building through sculpture and painting. It will also create a “living” fund to extend the congregation’s reach further into underserved communities of Boston. It is expected to take 2 years to complete.

The Memorial to Enslaved Persons, designed by Harmonia Rosales, in collaboration with Mass Design Group, consists of three parts:

– A figurative sculpture of a woman personifying freedom in the Chapel’s courtyard, holding opened birdcages with a scroll containing the names of the 219 enslaved persons at her feet

– A collection of 219 bronze birds perched throughout the church’s exterior and grounds, representing free-will, rebirth, and empowerment

– An immersive ceiling mural inside the Chapel’s sanctuary, depicting Black and Native people releasing birds into the sky

Links and Press Coverage on the Memorial

Brochure – King’s Chapel Memorial to Enslaved Persons

Old North Church

Illuminating the Unseen – A video series produced by Old North Illuminated that studies the histories of Black and Indigenous people. It shines a light on those who have often been excluded in the church’s broader historical narrative.

The Embrace

One of our private tour groups visiting The Embrace

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King met in Boston in 1952. The Embrace is a memorial to their love and leadership. It is inspired by a photograph of the Kings embracing when Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

The bronze sculpture was designed by artist Hank Willis Thomas and Mass Design Group. It is nearly 38,000 pounds, 20 feet high, and 25 feet wide, and is made up of approximately 609 pieces. The sculpture is grounded in a 6,000 square-foot circular plaza. The 1965 Freedom Plaza that supports The Embrace honors 69 civil rights and social justice leaders active in Greater Boston from 1950-1975. Many of them marched alongside Dr. King from Roxbury to the Parkman Bandstand on Boston Common, just steps from the memorial, on April 23, 1965. In his speech, before a crowd of 22,000, Dr. King called on Boston to confront racism and economic injustice.

Learn more in The Embrace Digital Experience